Feature policy: the web's missing guardrails

Principal Developer Advocate, Fastly

Over almost 30 years of its life, the web has grown beyond anyone’s imagination, and the platform has become immensely powerful and flexible. With that power and flexibility comes complexity, and the potential for slow or insecure websites to deliver a poor user experience that drives people away from the web. Feature policy is here to help, and we’ve built a tool to show you how to use it.

I remember when I started out in web development in the mid ‘90s. It was a Wild West. No qualifications, no certifications, almost no knowledge required to get going. I actually kind of miss it: now, new developers joining our global community of millions have access to extraordinary amounts of content, tools, and opportunities to learn from others, but at the same time, it’s harder to get something done if you’ve literally no idea what you’re doing.

This is a natural process. It’s growing up. When the early pioneers of aviation were designing planes, getting your dog to sit in the tail of the aircraft might make the difference between a plane that would fly and one that just wouldn’t leave the ground. Today, when you take a flight, you expect everything on the aircraft to be designed for the task, precisely engineered and certified, regularly inspected, and highly reliable.

As flying became more and more popular, it became unworkable for planes to fly wherever they wanted, or to sit on the runway for as long as they liked. We needed to establish rules and standards, not just to make things work, but to maintain equality of access and availability of scarce resources in a decentralised system. When no one is in charge, why would anyone obey the rules? This question is solved for aviation with international treaties and industry regulation.

The web has been gradually catching up, and while it’s often been rocky, involving power plays or less-than-ideal incentives, we’re slowly getting there.

Pop-ups, pop-unders: window whack-a-mole

Image source: Engadget

In the early days, it didn’t take web developers long to discover the window.open API and the ability to launch hundreds of incredibly annoying adverts using it. This is our first story of terrible incentives, and the tragedy of the commons is that if everyone else does it, you have to too. Ultimately browser vendors stepped in and limited the ability to open new windows to situations triggered by user interaction.

The inevitable demise of Flash

The ads may have been constrained to the one window, but by 2007 almost all ads on the web were powered by Adobe Flash, and would chew through the vast majority of the system resources used by the browser, because the site owner has little incentive to optimise the performance of the end-user’s device. With the advent of the iPhone, Apple famously decided to simply not support Flash, and in that moment, an entire SWF-producing creative industry died.

Perhaps it wasn’t that dramatic, but it was supremely effective. Today, very few web pages attempt to launch content using alternative runtimes. Even DRM video is now supported by the Encrypted Media Extensions open standard.

As with pop-ups, the solution again was coercion by powerful corporations, and luckily the solution in both of these cases left the web’s decentralisation and openness intact while adding guardrails and rules to keep the system healthy.

A dark turn towards the walled gardens

Still, individual web pages grew and grew, and the user experience became worse and worse. By now most of the world was online to some extent, and many simply could not afford to download a 50MB webpage.

A tiny number of companies now originated the majority of referral traffic for the rest of the web, so commercial content platforms that enforced good UX began to appear: Google, Facebook, and Apple all created their own content formats: Google’s proprietary AMP format became a requirement for news sites that wanted to feature above the fold on search results, and that meant allowing Google to host the content — as well as being forced to give up not just bad practices, but essentially all the cool parts of the web platform. Many developers were not impressed.

These kind of coercive interventions go against the ethos of the web, and the fundamental principles of no one having overall control or authority. Even when the intent is benign, using the power of the web’s largest companies to decide what’s best for its users isn’t actually good for its long-term health.

Feature policy to the rescue

Today’s web is extraordinarily powerful, and the potential to be a bad citizen of the web is as large as it’s ever been. Browsers are now some of the most sophisticated pieces of software on earth, and yet it’s still possible for me to write a webpage that will prevent you from using an ad blocker, slow down your computer to a crawl, or download a huge amount of data in the background. Having not learned the lesson of pop-up windows, we unwisely added the Notifications API, and now websites have started asking for notification permission the moment you open the page, leading to browsers allowing users to turn the feature off entirely.

We need, as a community, to identify practices and features that are expensive, sensitive, or invasive, and give developers a way to disavow them easily. At the same time, we need to avoid heavy-handed actions that disenfranchise the development community, while providing incentives to adopt the better practices. This is what Feature Policy is designed to do.

What’s in a policy

Policies are keywords that relate to some behaviour that a website can choose to exhibit. For example, although considered a bad practice for years, many things on the web still use the document.write API, to insert dynamically generated HTML programmatically into a document as it is parsed. The problem is, this triggers the browser to re-parse the document, making the website run slow. A developer wanting to ensure that their site does not do this, can now include the following HTTP response header along with the document:

Feature-Policy: document-write 'none'This achieves two important things. First, it avoids costly and manual auditing processes that would otherwise be required to police this best practice (and will also identify immediately if any imported code or new third party tools violate it). Second, it signals to browsers and web crawlers that you intend to comply with this policy.

This allows good practices to be more easily rewarded, say with higher search placement, or a positive badge of endorsement for speed from a search engine or browser. Perhaps complying with certain policies might enable placement in a directory, automatic preloading, or richer previews when links are shared on social media.

Generally, the policies agreed so far fall into three categories:

Powerful or permission-requiring features:Things like access to payments, autoplaying video, camera, geolocation, or wake lock APIs should not be done casually. Having a policy allows developers to avoid triggering permission prompts that they don’t intend to bother users with, prevents third parties using them without your knowledge, and reduces the attack surface for vulnerabilities in those APIs to be exploited.

Sandboxing iframe behaviour: Some features are not too powerful, but you might reasonably want to deny them to subframes of the document. For example, you might want to prevent an IFRAME from navigating the top document, or submitting a form.

Bad practices:

document.writeis a good example, but there are so many things we can precisely describe, easily detect, and which are nearly always a bad idea. Others include loading script in a blocking way, or loading images that are natively much larger than the frame you are trying to render them in

The full set of policies that have already been implemented is available to explore in our Feature Policy playground, where you can see the effect of allowing and disallowing various policies.

This framework is so generically useful that we’ve barely scratched the surface of the possible policies that could be created. I’d like to see policies that govern behaviours such as:

unsolicited-permission-request: Requesting access to an API that requires explicit user consent, without being initiated by a user interaction. This kind of behaviour would include requesting notification rights on page load.top-navigation: The ability to navigate the browser to a new document programmatically. This is likely to be something that documents would prefer to disallow within IFRAMES, for example.large-media: The ability to load large (say more than a total of 2 MB) of image, audio and video resources as part of the document load waterfall. Videos that preload only metadata and then start downloading when the user initiates a play action would not count.

None of these policies exist — but they give you an idea of the kind of thing people are talking about, in this big discussion of how we can start to bake our common understanding of ‘best practice’ into the platform itself, without breaking anything.

Incentives

So what would convince developers to adopt strict feature policies? Some will anyway, of course, but if Feature Policy is to improve the general health of the web, and the trust and engagement that end users have with it, then we need to bring everyone along.

This is where search engines and other traffic-referring organisations can help. Search results could be badged with some approving ‘fast’ logomark or (more controversially perhaps) get a higher result ranking if they disallow themselves certain policy-controlled behaviours.

A strict feature policy set might also communicate to social media platforms that a site is lightweight enough to generate a rich preview, or to embed directly within another experience. If you wanted to make this possible, you may need to comply with that policy.

Measuring up the sites of today

Today, of course, many sites use the patterns that are starting to be ring-fenced by Feature Policy. Let’s look at Le Monde, one of the world’s most respected newspapers and a Fastly customer. Using a tool such as Charles proxy, we can inject a Feature-Policy header into HTML pages on the site. I added this one:

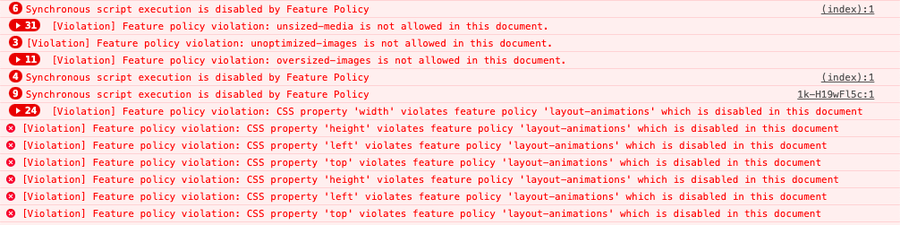

Feature-Policy: autoplay 'none'; document-domain 'none'; document-write 'none'; font-display-late-swap 'none'; layout-animations 'none'; legacy-image-formats 'none'; oversized-images 'none'; sync-script 'none'; sync-xhr 'none'; unoptimized-images 'none'; unsized-media 'none'This is pretty evil of me, honestly. I’m disallowing every antipattern that Feature Policy has guardrails around as of today, and many of these are not even beyond proposal status, requiring Chrome Canary with the experimental web platform features flag enabled. Let’s see what happens.

Generally the site looks pretty good, but we can see the images are not loading, and we are also missing out on some ads that would otherwise have been visible in this view. What does the console say?

It turns out that the policies triggered by Le Monde are similar to those triggered by most modern websites. Every major site I tested required sync-script, and many trigger the image-related policies: unsized-media, unoptimized-images and oversized-images. Le Monde also includes some layout-triggering animations, which require the layout-animations policy to be allowed.

Try it with your site

If you want to see how your site deals with Feature Policy, try setting one as an HTTP header. If you’re a Fastly customer, you could add this to your configuration:

We’re excited about Feature Policy as a way to help our customers keep their sites fast and secure, and improve the web for everyone.